Meet the Small City in Wyoming Where Photovoice is Becoming A Force for Good

There is a quote often attributed to the anthropologist and author Margaret Mead that goes something like this: “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it’s the only thing that ever has.” One of these groups of small and committed individuals are the community leaders behind the Center for a Vital Community (CVC), a program of Sheridan College (Wyoming) using photovoice along with other tools to empower people to engage in and strengthen their community.

That’s a process that begins by helping people and communities to see deeply. By seeing deeply into important social problems in their community such as youth mental health, an influx of new community members reshaping the status quo, the Center for a Vital Community empowers community members to navigate change.

“[The photovoice experience] helped me view what other people view differently, and their experiences. But mostly on how they interpret the areas surrounding them and what makes our tight knit community [special] to them,” Emily Gorzalka reflected, a project participant.

In 2021, Interfaith Photovoice and Essential Partners received a grant from the Fetzer Institute to design a new approach to dialogue combining Interfaith Photovoice’s tools orbiting around amateur photography and dialogue with Essential Partner’s use of reflective structured dialogue. The integrated approach became known as Essential Photovoice. A team of facilitators from the CVC was the first of 12 communities trained through this grant.

Sheridan is a rural town with a population right around 20,000 in Wyoming on the heels of one of the most divisive elections in American political history. “In 2016, when civility was disappearing, we decided that we wanted to focus on how to have constructive conversations around hard topics,” remembered director Amy Albrecht. It’s in this heated context that the Center for a Vital Community stepped in to model and innovate the new dialogue approach.

The CVC is nourishing important work around civility and community in their small Mountain West town. “There are so many of us coexisting who utilize the same spaces, people, and resources in slightly different ways, but with a common purpose. We are more similar than unalike; we have differences and different wants, but our needs align. There is space for each to exist. Seeing someone completely different than I [having] a similar picture makes [the] community feel positive,” said Emily Julian, a participant in one of the center’s community photovoice projects.

Such testimonies are commonplace with the work of the CVC — work that has included six (and growing!) unique photovoice projects and countless photovoice activities.

The first project, The Changing Faces of Our Community, focused on flourishing at a time of community change. The 24 participants came from all walks of life and carried with them a richness of diverse identities. Interfaith Photovoice and Essential Partners trained six facilitators from the CVC to run an Essential Photovoice in Sheridan. What united the group, through differences of politics, religion, race, and more, was a heart for community engagement and a desire “to share and learn more about this community that they love,” said Julie Davidson-Greer, the CVC’s Project Coordinator.

Those involved with the project are no longer able to see their community the same way as before. They see so much more than the myopia of their own perspectives enabled. “When you drive through town, what are you seeing now? What kind of things can you not unsee? Those are the conversations and perspectives people got [from the project],” summarized Albrecht.

The CVC is no stranger to wrestling with big, important issues and their second project, in coordination with a local high school, reflected that. The project recruited a class of high school students to take photos and reflect on youth mental health. The project helped students to learn about and experience empathy with others’ mental health challenges, normalize talking about mental health, and to help others realize they are not alone in their struggles.

The project reports and feedback all attest to a tremendous impact on the students who felt encouraged to discuss their feelings around mental health. One student shared, “I am scared to get old.” Others talked about mental health struggles, traumatic past events, and the relationship of their life goals to their present studies. The vulnerability was remarkable.

One high school student was brave enough to share with his classmates a powerful photographic story related to his previous suicide attempts. The student shared his photos with his small group because he felt his story would resonate with others. He was right. He was not alone in his stories. While his photos were not included in their exhibition, his photos still made a difference. Later, at a parent-teacher meeting, this same student asked his teacher if he could show the photos from the photovoice project to his mother. His mother was learning a lot of very important information about her son for the first time. Information that helped empower her to be an even stronger support system for her child and to seek any help needed.

This kind of brave, even heroic, vulnerability is rare — and even rarer amongst high school students, where peer pressure and bullying often discourage such vulnerability — and still, photovoice helped this student to find his voice.

Brandon Bond, Mental Health & Well-Being Project Lead at the University of Michigan and trained photovoice facilitator, points out how photovoice can be used to help participants express their thoughts and feelings when they don’t have the language to convey it and that process can lead to creating spaces and networks of support to those that may need the support. “At times, it can be difficult for people to effectively verbalize what's happening to them in physical, mental, and spiritual senses. Think of trying to put a puzzle together without a clear image of what the end product is. All the pieces are there, but if someone asks you to explain what it is, you'd likely struggle to provide a quality explanation. The same thing happens with our mental health. We have all the pieces (our thoughts, emotions, and experiences), but we can feel stuck with the verbalization and meaning-making process that's needed to help others understand what's taking place.”

But photovoice, as shown in through the story of this courageous high schooler, can be used to intervene and open paths to understanding individuals in need on a deeper level. “Photography and other art forms can serve as a critical source of expression for people and help them to convey their inner thoughts in a more tangible and framed way,” Bond adds.

“This invites curiosity and connections, as opposed to harmful reinforcement and isolation. Each photo taken is almost like figuring out one of the corners of the puzzle; it's not a full view, but it gives a small glimpse into someone's reality,” Bond observes. That’s also why we share one of these sensitive photos here.

This work changes lives.

This second project was a success and also a learning moment. The leaders of the CVC acknowledged a general feeling that emerged was that the process was “very heavy” and because it took place so early in the school year when relationships were still in formation, the project would have benefited from a less heavy topic that the students themselves were able to help identify.

“We continue to learn so much as we go along with these projects,” Albrecht added. “One thing seems to be clear [is that] the students who self-select to participate are a lot more invested in the process/project than the students required to do it as part of a class.”

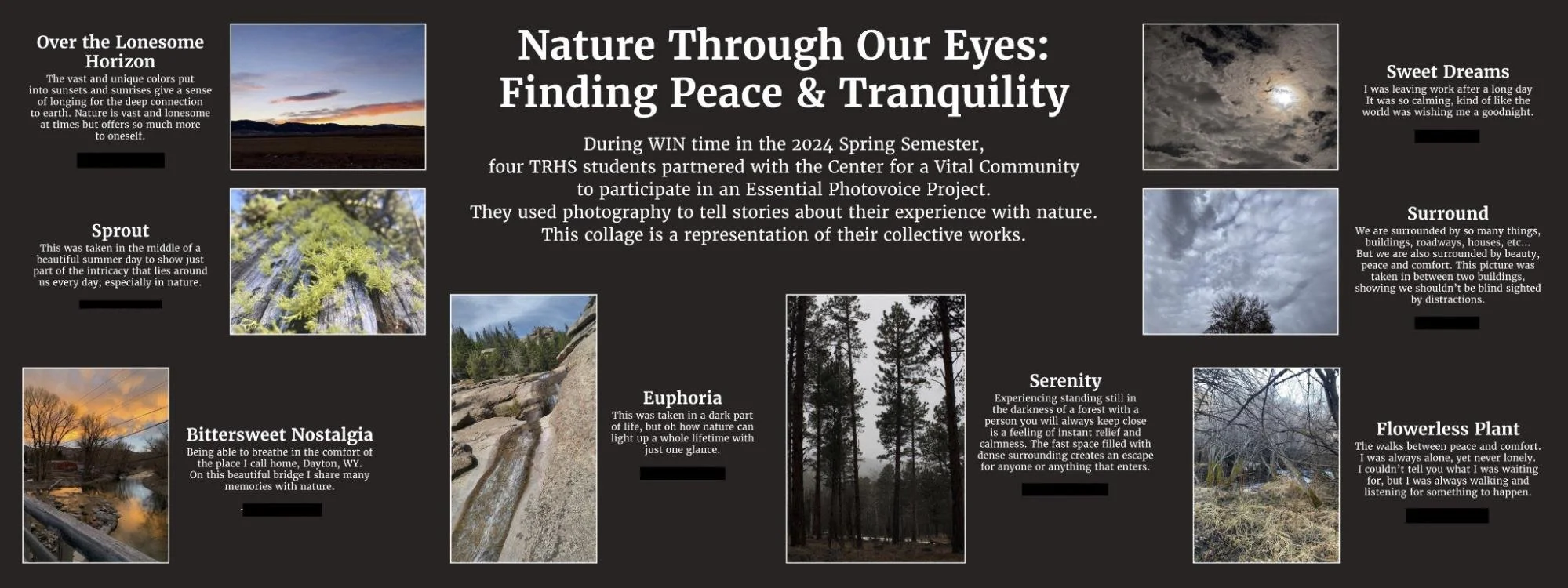

One of the key takeaways they had from the mental health project was allowing the participants to have more of an influence in the subject matter of the project. So, in their next project with a school, they allowed the students to pick the overarching focus of the project. They selected nature, just narrowly beating out a theme related to “girlhood” (all the participants were all young females).

While the project was still a success, the facilitators at CVC felt there was a layer of vulnerability and significance that the chosen topic prevented them from reaching. “Where we learned that we shouldn’t impose a topic, we also learned that we shouldn’t 100% let them pick a topic with no guidance,” said Davidson-Greer.

The facilitators learned a lot in the process and the participants loved it! They took ownership, listened to each other’s stories and responded enthusiastically with their own, and they found the artistic outlet empowering.

Emily Gorzalka, high school senior, fondly remembers participating in the project, “It helped me understand everything in the community at a deeper level. It's not just seeing people come together but by seeing their photos and hearing and engaging in the conversations, I have a better understanding of my community and the individuals in it.”

The first step to change is “identifying and illuminating area issues,” as the CVC website puts it. And by combining amateur photography and structured dialogue, the CVC has been able to do just that. They have invited 65+ community members into constructive dialogue around difficult subjects, and they have opened many more conversations into key issues, including with their many public facing photovoice exhibits. One project participant summarized the importance of their work: “Essential Photovoice was a great opportunity to conduct a civil conversation while listening to different perspectives on our community.”

Photovoice has become such a staple of the CVC’s programming that they recently hired and trained Sylvia Howard, a senior at Sheridan High School, to help run photovoice activities in three projects during the 2024-2025 academic year. Sylvia has been helping to recruit participants, coordinates project logistics like printing photos before meetings, and participates or helps facilitate when needed. “[Sylvia] has been working hard all school year to be sure [our photovoice projects] are successful,” said Albrecht. “We would not be able to do three local high school projects this spring semester were it not for Sylvia's efforts.”

The CVC has made the most of their photovoice training, using the tool to transform their community into a vital community. “The training we received set us up for success with every project that we’ve done. Even when we hit roadblocks, we have the tools to overcome them,” said Albrecht. Learn more about our training process and how you can use the same tools to impact your community on our website.